The history of photography in the Harvard Advocate is an ongoing and rich one, a confrontation of the enduring question: How does the image find its place in a literary magazine? To commemorate the launch of The Harvard Advocate’s Winter 2013 issue, “Origin,” we have traced the emergence and changing role of the image in the Advocate and the ways in which the photographic image has been read on the page.

Although photography had emerged in print in the early twentieth century, photographs only first began to appear in the magazine during the fifties and sixties as illustrative content and as advertisements. A portrait of T.S. Eliot was included in the centennial issue, used as a visual reference to one of the Advocate’s most esteemed alumni. All of these examples speak to the then secondary, supplementary nature of visual media to the magazine.

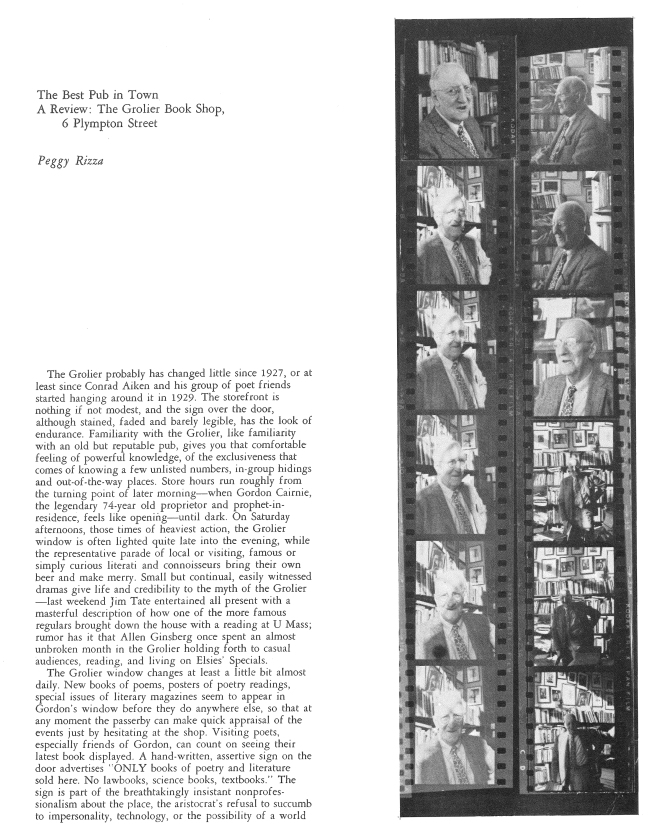

Yet even at this point, photographs were quietly gaining more momentum, energy, and impact. Photos were featured alongside interviews with literary luminaries such as John Berryman (published in the Spring 1969 issue) and Conrad Aiken (published in the October 1970 issue).

This particular spread of this October 1970 issue marked a particular moment in the institutional use of the photograph in the Advocate, as the image was now distinguished from the content it had been informing. On this page, the film reel vertically flanks the text of the interview with Aiken. With the sprockets visible, the set of pictures remains raw, and the seriality of the portraits lends a new agency to the photograph, which now tells a story of its own. Rather than being edited, this printed film negative bares it all, without attempting to hide what wasn’t used. Instead, this image embraces the processes that both interviews and photography require.

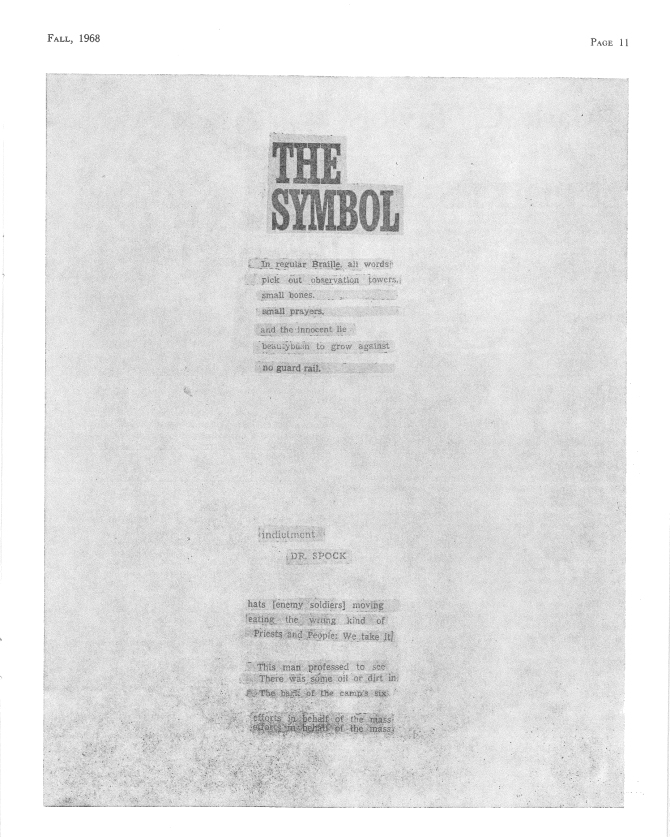

These years, between the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, marked a radical transformation in the use of visual media in the Advocate. Photographs began to be published more frequently, though they still often remained as supplemental material. The photographic image had seldom existed by itself. “The Symbol,” published in the Fall 1968 issue, can be seen as the turning point that gave photographs their own voice in the magazine.

“The Symbol,” a reproduction of a collage of pasted text, was one of the very first images printed on its own without any captioned text. Here, the text becomes the image—the text is the image. The two media coexist and mutually enhance each other, as photography becomes the vehicle through which the poem is reproduced and published. Photography acts as the means for reproduction of a poem of visual ontology. Poetry had prompted the publication of the photograph as a form of its own craft.

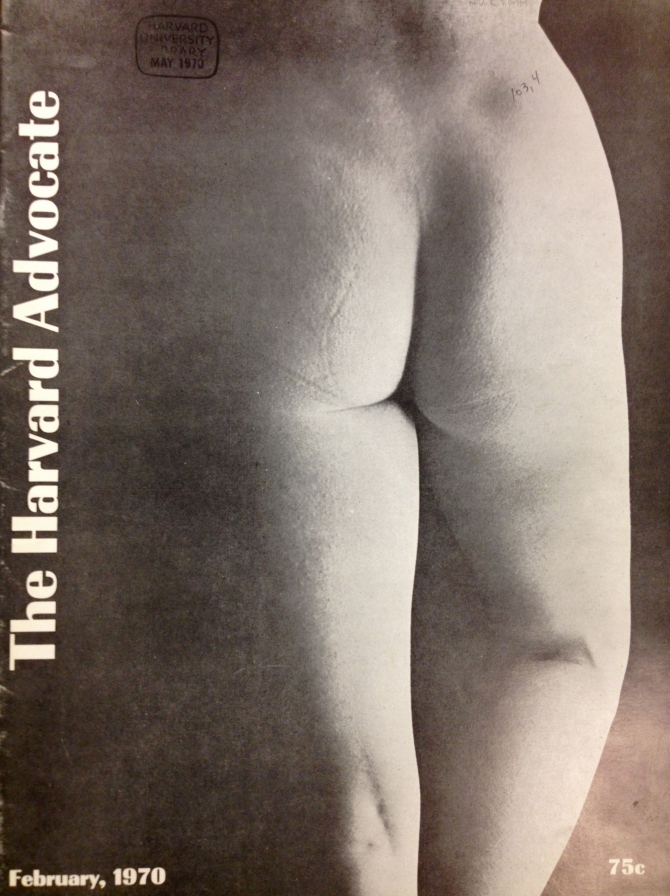

This piece speaks to the growing importance and centrality of photography to the magazine. The Vietnam War and the revolutionary voice and spirit of student counter-culture of the ‘60s and ‘70s set the mood for the shifting direction of the magazine. James Atlas, 1968 president of the Advocate and current chairman of the Board of Trustees, chuckled as he remembered photographic media emerging in the pages of the magazine. Atlas recalled one particularly edgy photographic cover published in February 1970, describing it as the “nude backside of a woman, that’s a good name for that.”

Moving on from such levity, Atlas took time to reflect upon the larger role that photographs played during his tenure on the Advocate. His time in college took place within a context of social radicalism, Atlas remembered: “One of the powerful motivations was to be scandalous, not intellectually provocative.” Through the increased inclusion of visual media, he hoped “to somehow have the Advocate, for all its endearing stuffiness, reflect what was happening outside our windows, quite literally.”

In a literary magazine, the focus often lies on the words. Text tends to frame images, through captioning, explaining, and contextualizing. The then-racy 1970 cover of the magazine of the bare backside of a woman speaks to the ways in which the photographic image can color how something is read.

Beginning with the renegade spirit that helped photographs gain steady footing as an integral part of the publication, visual media in the Advocate have since continued to evolve. They remain a part of the rich artistic tradition that the magazine continues to publish today. In the Winter 2013 “Origin” issue, “Ellen’s Gift” is a parafiction, a photo essay that operates in the space between fiction and reality, that poses as if it documented the story of a real woman. Current photographs in the Advocate have found their contemporary edge.

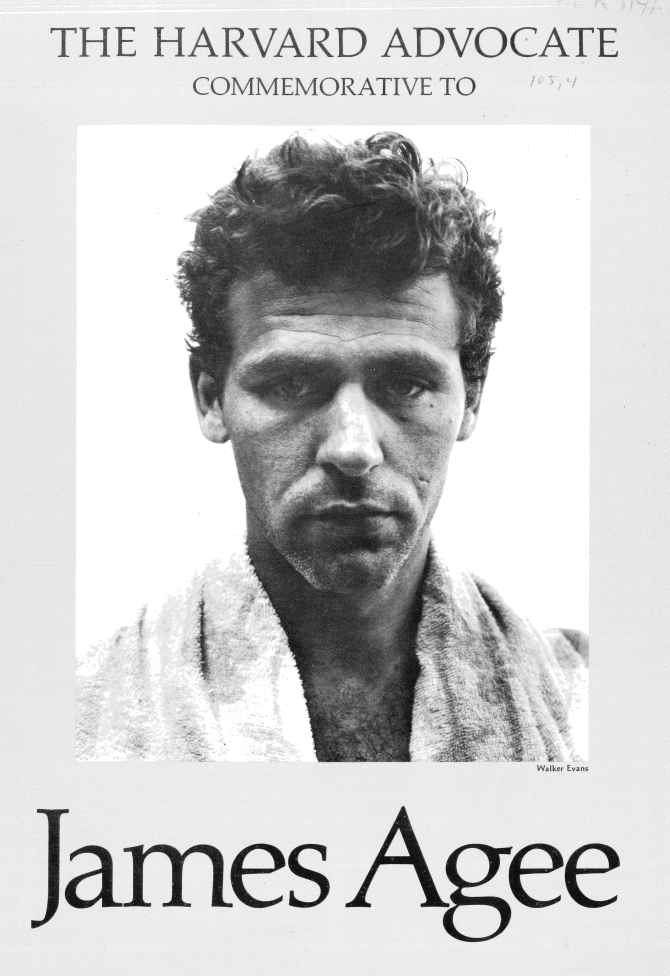

In meditating upon visual media in the Magazine, it seems only fitting to honor 1932 president James Agee, renowned American art critic and media theorist. In 1972, a commemorative issue to James Agee was published that highlighted his theoretical works on visual media.

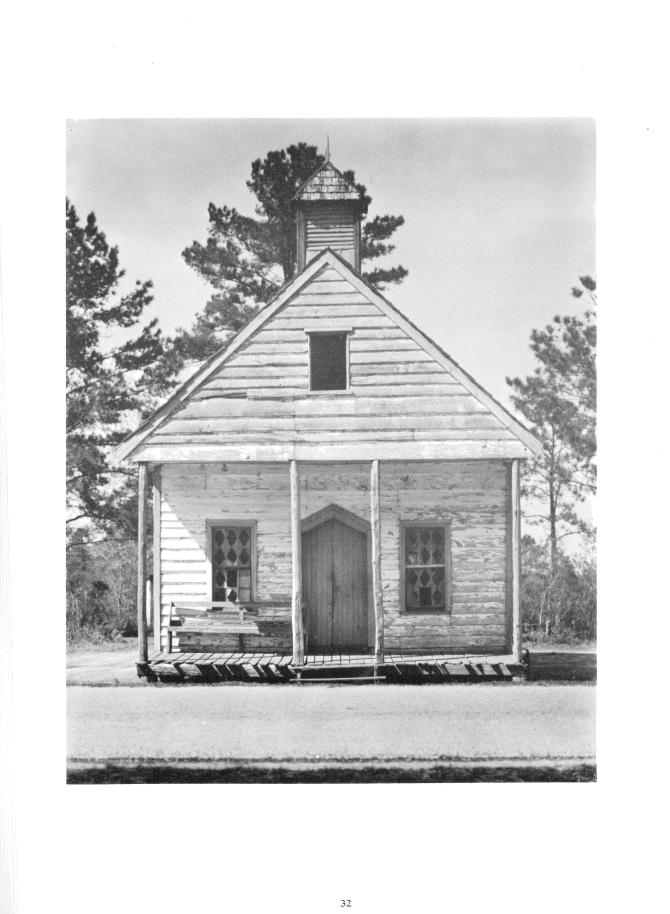

Photography at the time was still relatively new in the Advocate’s institutional memory. Agee had written extensively about the photograph and the ways in which the viewer comes to appreciate its meaning. In reference to a Walker Evans photograph, taken when he was writing Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee writes about the struggle of verbally discussing and analyzing photographs. For him, “The whole problem, if [he] were trying fully to embody the house, would be to tell of it exactly in its ordinary terms.” To caption a photo limits the photograph’s possibility, reducing it explicitly to a lowest common denominator; something is inevitably lost. An ineffable photographic effect remains that cannot be put down on paper.

Agee’s discussion exposes the underlying irony of any analytical exploration of photographic material. This short piece serves as a footnote to photographic highlights of the past. But perhaps, this series of ‘explanations’ dilutes the possible potency of visual media in the Advocate itself.

Is a picture worth a thousand words? Or should a picture simply leave us speechless?

Let us blink, and with fresh eyes, savor the silence.

By Ezra Stoller ’15 and Edwin Whitman ’15